This is part one of a series called Mapping Histories.

With twenty-four hour news cycles, this site events frequently forgotten or repeated, and the seemingly endless churning of information, styles, fashions, and fads—the question arises: what does history mean to us now? What is our relationship to past events in the context of ubiquitous hyper-technologies, mediation, and rapid forgetting? Can technology help make sense of the historical archives—to draw a line from the past events to the living present? Interactive history maps are uniquely able to access to our collective past and provide insight into these questions. These types of projects represent some of the ways that the study of history has changed over the past forty years and will be the focus of the following exploration.

Since the 1970’s, varied academic disciplines vigorously turned towards new ways of approaching and interpreting their subject. In the humanities, there have been a series of turns that reshaped the way that human activity (culture) is studied; two of these turns are the spatial and computational turns. The spatial turn1 meant applying geographic principles and techniques to cultural material to understand how human activity exists, expands, develops, and interacts within its specific geographic contexts. Previously, cultural artifacts were often studied through temporal lenses: divided in specific eras, time frames, schools of thought, groupings, and genealogies. Before the spatial turn, culture was rarely understood within its place-specificity or compared to other geographies. The other crucial change in scholarship was the adaptation of emerging technologies toward scholarly studies, now referred to as the computational turn.

The computational turn emerged through the use of computational and quantitative technologies applied to the study of human activity to provide new perspectives. Events can be graphed, mapped, and visualized in order to pull new and additional meanings and relationships out of the material. This combination of the spatial and computational turns has culminated in a particular practice?the use of map APIs (application programming interfaces) to build web-based projects that help people to understand historical events. Mapping is but one of many new research methods being employed along with text-mining, web-archiving, and crowd-sourced social histories projects. Researchers and hobbyists alike have built these tools to understand urban change, contextualize local events and communities, and even reveal added dimensions to family stories.

There are many competing map APIs: Open Street Map, Bing, Polymaps, Mapquest, and of course, Google Maps.2 Each of these platforms uses similar technologies to create their maps and often times improvements to one platform filters its way down to the others. Google Maps, due to the scale and funding of its parent company (Google), has become the defacto consumer map tool, offering users the ability to customize, import, and display many types of spatial data. The reliance on Google Maps API may prove problematic because changes to the platform or the terms in which it may be used can easily jeopardize or break the many projects built upon it.

All of the following examples use the Google Maps API despite a wide variation between the look of their user interfaces. Each of the below web-based projects provide a platform for placing photographs onto the map. Each website has regional differences in terms of content and dependent on the user-base. They use various strategies to obtain data, either through crowd sourcing or acquiring access to public/private archives, present the data for comparison and to accurately label, locate, and categorize the material.

Old SF connects San Francisco historical photographs to their places of origin. It was constructed with the San Francisco Public Library’s archives of street and architectural photography, displaying photographs from 1850-2000 in a side bar and with a corresponding point on the map. Users can choose the dates of the photographs by using a slider to constrain the range of results. Retrographer is a Pittsburgh, PA centric project built by a student at Carnegie-Mellon University. Like Old SF, it offers historical photos and a slider to constrain results from 1890-2000. Retrographer displays historical photos side–by-side with a current photo for comparison along with a map view. It remains one of the cleanest interfaces of the projects under discussion. It also allows users to discuss and comment on photos and to help identify the location of photographs when the location is unknown.

Sepia Town, What was There, and History Pin are three more projects that are global rather than place-specific. These projects are open platforms featuring rich interfaces that a broad group of users can contribute to. The projects place photos on the map, offer comparisons, street views, and additional information on the photographs. Both Historypin and What Was There also have mobile apps to allow users to contribute to and to use their tools on their mobile phones. History Pin is also adding support for video clips and other forms of media that can be pinned to locations.

Alternately, there are two projects that take the birds-eye view to spatial histories, placing historical maps on current grids—showing such things as long-forgotten streets, city walls, grid realignments, street renaming and even developments that were scrapped. Hypercities was developed by a team from UCLA and other southern California educational institutions. It focuses on earlier historical maps overlaying maps from as far back as the 16th Century. These include hand-drawn early cartographer’s renderings alongside more modern surveyor’s maps of particular places. PastMapper is new project by Brad Thompson and John (aka burritojustice) featuring historical maps and places of interest in San Francisco. This project is still in early stages3 but is trying to provide a fine-grained look at “what was here” by reconstructing the historical city grid and matching points to historical city records. One innovative feature is the ability to toggle between San Francisco’s current grid and its grid in 1853.

These types of projects are rapidly proliferating and provide a unique way to publicly access historical material. There is support from many museums and public archives for these services as archivists look for new ways to share their resources. Mapping applications like these are clearly valuable platforms for individuals to share stories and materials, open up family archives and community histories. These tools also make it easy for non-programmers/cartographers to see maps and histories in a particularly tangible and exciting way.

Tools like the above also serve to problematize history. History has exploded in million fragments. Capital “H” history is generally considered false or incomplete in the sense that it is always the narrative of the victorious. The alternative is the multitude of histories that fill-in specific lost details or compete with the official narrative or provide new angles for study. The revaluing of local and social histories has made the study of history both more complicated and also more interesting. No archive is honest or complete but by mapping available historical archives, yet another relationship to our past can be formed, studied, and participated in. In the specifically urban context that these projects cover, the past forms of streets, buildings and lifeways are put on display for comparison or novelty. These projects serve to highlight many of our histories, let us learn from them and let them live on together side-by-side on the internet.

Part two will focus on constructing narratives through local history walking tours and historical markers

notes

[1] For an excellent overview of the spatial turn see Jo Guldi’s What is the Spatial Turn?

[2] Bing.com, Polymaps, Cloudmade, openstreetmap.org

[3] Many of the people behind these projects were at the Bay Area ThatCamp in Mountain View.

(Inspiring work.Thank You!)

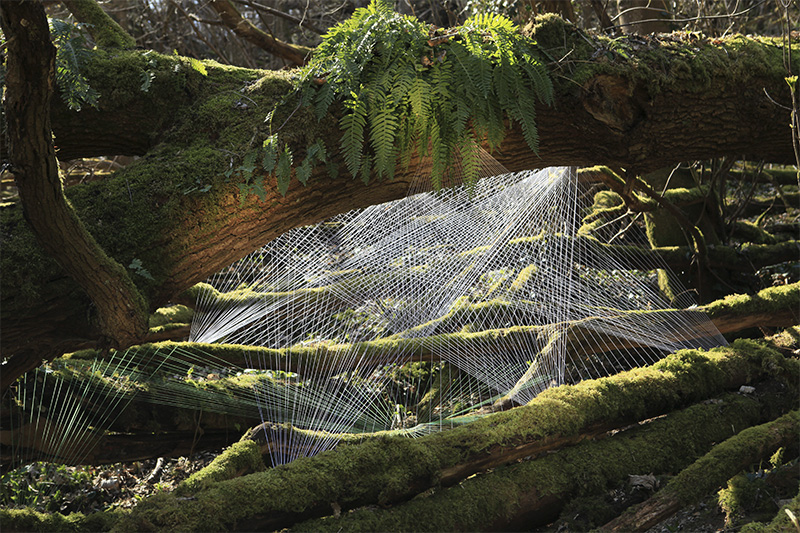

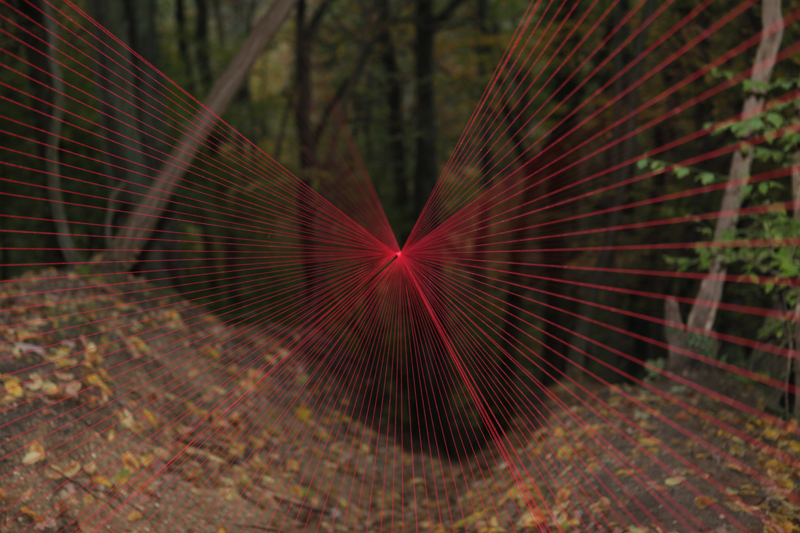

Remember the Spirograph? The plastic geometric drawing tool has for generations provided hours of hypnotic entertainment by helping children draw complex patterns on paper. French artist Sebastien Preschoux has taken the technique to a whole other level. His flat works and wall installations use the ethereal lines to create those same intricate and hypnotic patterns in a variety of colors and scales. More compellingly, visit he works in three dimensions, side effects using colored yarn to create these patterns in space. The best examples of his work are where the installation happens in unexpected places. For example in a forest at night. The strings reflect light and create bright vectors bursting from a center point. These outdoor installations create a perspective-shifting experience in the viewer that defies expectations. More of Sebastian Preschoux’s work here