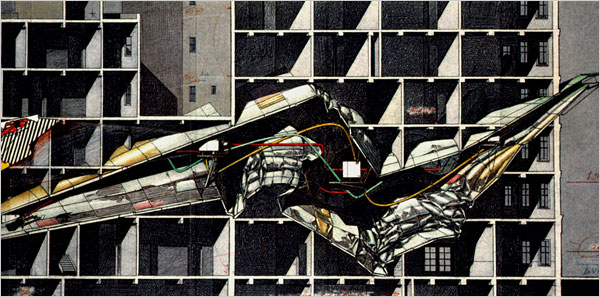

Lebbeus Woods, Berlin Free-Zone 3-2, 1990

Lebbeus Woods was a singular figure in architecture. He was an outsider, yet quietly influential to architectural thinking over the past three decades. He was a humanist, a deconstructionist, a utopian, a critical thinker, and often misunderstood. Lebbeus asked radical questions of architecture, questions that Architecture as a discipline was hardly capable of answering. His death in November, 2012 struck a chord with many, and yet he was not terribly well-known outside of certain academic circles. His massive output was primarily as a paper architect, leaving behind a mass of drawings, sketches, models and installations. One of the only buildings realized was his Light Pavilion (2008) that was integrated into Stephen Holls’ Raffles City Complex1 in Chengdu, China. Despite this his project was much, much larger than building things. It was about theorizing space and understanding humanity, pushing the possible over the horizon of staid limitations. He remained committed to an understanding of architecture as a design process that can transform space and human relationships.

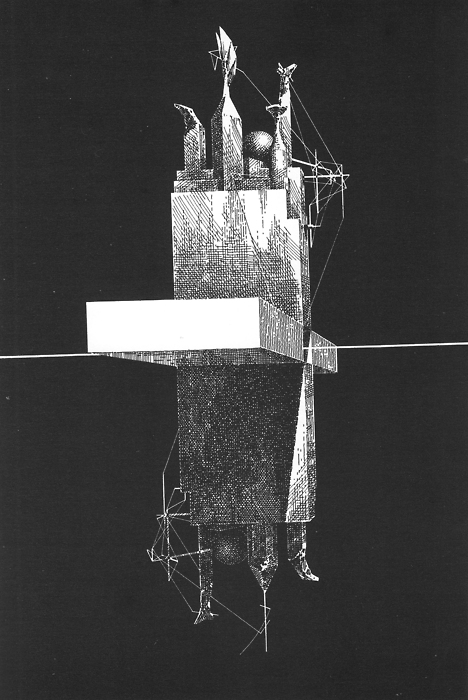

SFMOMA’s Architecture and Design department has assembled the largest collection of Lebbeus Woods’ paintings, drawings, prints, and models. Lebbeus Woods, Architect brings together many of these works for the first time. Curators, Jennifer Dunlop-Fletcher and Joseph Becker were already working with Mr. Woods to create an installation at the time of his death. In light of his sudden death, they assembled the current exhibition instead—a fitting survey of his many works. The exhibition features more than one-hundred fifty drawings and models including Centricity(1987-1988), A City Sector(1984-88), Aerial Paris (1989), War and Architecture (1996), Inhabiting the Quake(1995), Zagreb Free Zone (2001), and Conflict Space(2006). Each project tells a similar story by re-imagining the local conditions of places like Havana, Vienna, San Francisco, Zagreb, Sarajevo, or Berlin. Almost all of his drawings have inscriptions—poetic and philosophical fragments, personal notes or half-thoughts that indicate a very personal yet systemic notation system. Also on display are models of Einstein’s Tomb (1980), Meta-Institute (1996), Nine Reconstructed Boxes(1999), and Light Pavilion(2007). These architectural models invite viewers to get lost in their tiny cutouts and weightless, impossible geometries.

His aesthetic was fueled by science fiction and past utopian forms. Most works are composed of visceral lines, shattered planes, fields of networked and interdependent vectors. Some are pure speed and mechanical chaos, others emerge as an organic hybrid. Lebbeus Woods, Architect is a joy to explore in all its little details and the ability to see the evolution of his craft. These drawings and models became his way of grappling with the complexity of post-modernity. As he saw it, the conditions of humanity deserved his thoughtful attention and his output reflects this orientation. Lebbeus was obsessed about war, environmental catastrophe, crisis, and its effects. He was not alone in these obsessions:

Paul Virilio and I, in our different ways, share an intense interest in the changes brought about by technological innovation, by cultural and social upheavals, by natural catastrophes like earthquake and the social and architectural responses to them. I see these extreme cases as the avant-garde of a coming normality, one that we must engage creatively now, inventing new languages, rules and methods, if we are to preserve what is essential to our humanity, that is, compassion, reason, independence of thought and action.2

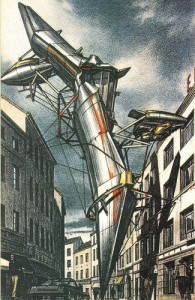

Lebbeus Woods, Zagreb Free Zone, 1991

Reconstruction was a question he frequently thought about, especially after the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. He was deeply moved by the destruction of Sarajevo, and the fall of the World Trade Center ten years later on September 11, 2001. His projects over this period focus on the continual questions faced by people reconstructing their lives after catastrophe; meeting needs, understanding loss, and recognizing trauma. Lebbeus’ writing on catastrophe pointed toward architecture built for remembering what was there and what had happened, to enable a looking back while moving forward, not as a dead monument to history, but of life moving on after disruptive events.

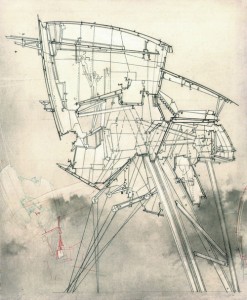

Likewise, the seed of his political project was to understand the construction of space in response to or in spite of disaster and destruction. Singular buildings or architectural forms are way less important than the relationships between people and space; or in his own spatial term, the field. He states that,

Architecture creates a field of potentials, defined by spatial limits, and also by its own imbedded methodology, within which people may choose to act, or not. Traditional architecture tries to choreograph people’s movements, even their thoughts and feelings. The architecture I envision is more anarchic. For some years I called it freespace, free of predetermined purposes and meanings. The difficulty of occupying such spaces confronts the crisis of contemporary existence, namely the necessity to invent one’s self and meaning in the face of world-destroying changes.3

Freespace was a clear signifier of his relationship to the historical avant-garde and its later utopian variants of every social tendency. His War and Architecture Pamphlet and Radical Reconstruction monograph were manifestos of reclaiming space and presented cursory models of inhabitation after catastrophe. His thinking aligned with de-constructivist and post-modern discourses, both popular at the time they were written. His philosophical trappings were simultaneously very contemporary, yet remained both sincere and ethical in an avant-garde or classically modernist tradition. His writings should be read with those of Paul Virilio and Manuel De Landa, authors whom he worked with directly. Philosophy plays a large role in his thinking and threads of Nietzsche4 , Derrida, and Gilles Deleuze help to illuminate his explorations. Lebbeus’ broad influences helped him to understand the destructive role of technology, the violence of war, the struggle of humans against powerful forces within and outside of themselves, and the transformative possibility of creating models of something radically new.

Lebbeus Woods, High Houses, 1995-1996

Wood’s detractors only seem to see his aesthetic sensibility, reducing him to a science-fiction concept artist and willfully ignoring the decades of writing and theorizing. He did create concept art for Alien 3 and illustrated the occasional science fiction book, but these were only a fraction of his output. His importance was as a complicated voice within the architectural discourse, someone with a unique vision of what architectural practice could look like. In a moving presentation by his former colleague, Anthony Vidler, viewers were encouraged to see the struggle behind the drawings, to understand where Woods was coming from and what problems he faced. He was described by Vidler as a solitary thinker, and solitary artist but one with a fierce commitment to collective action and a faith in social transformation.5

Over the past five years Lebbeus turned to blogging as a way to vet his ideas and be part of an intellectual community. His archives are a testament to his engagement with the larger questions that preoccupy architectural thinking and to the breadth of his knowledge and interests. He shared some of his own work on the blog, along with projects he found interesting, essays, interviews, and fragments of ideas he was working on. He seems to have drifted away from an understanding of buildings themselves as being transformative into a richer understanding that what is needed are new models for thinking and doing.

His unique position as artist, architect, educator, and philosopher meant that his ideas managed to resonate across disciplines. Lebbeus reminds us that “Living experimentally means living continually at the limit of received knowledge” 6 and his vision for a better world will no doubt be continually rediscovered for decades to come.

Lebbeus Woods, Architect is at the SFMOMA until June.

Lebbeus Wood, Einstein’s Tomb, 1980

Notes

(1) Video of Steven Holl on the Raffles City Complex Leb’s Light Pavilion is at 5 min. mark

(2) “As it is: Interview with Lebbeus Woods”

(3) ibid.

(4) Sanford Kwinter on Woods

(5) Anthony Vidler spoke at California College of the Arts on 2/18/2013 (link)

(6) Lebbeus Woods, onefivefour, Princeton Architectural Press. 1989/2011. pg. 3.