Environmental Health Clinic & Sentient City

The Environmental Health Clinic + Lab (X-clinic) is an interdisciplinary, more about stuff experimental, price community-based project with institutional backing from New York University. It is directed by Natalie Jeremijenko, an artist, educator, and scientist who for over two decades has brought together disparate disciplines with a particular sense of graceful convergence.

The X-Clinic’s operating principle is to turn the idea of health care on its head, shifting the idea from internal medicine to external interventions for health. They ask the question, what can we do in the face of collective and recurring damage? This particularly ecological model lends itself to broad-based experiments and solutions to community problems. The X-Clinic’s projects are oriented towards long-term future thinking fusing art, design, hard sciences (chemistry,biology, ecology) and community participation. Many of the projects serve a practical short and medium-term goals such as sequestering toxins, recording environmental data, plantings, etc.

It is difficult to ascertain whether their endeavors are well received, because they are either extremely successful or are simply experts at image management, but the perception is that Jeremijenko and company deftly fuse a number or different disciplines to great effect. Their website seems dormant since late last year leaving it unclear if it is still an active project but either way it represents an intriguing way forward for the integration of arts, sciences, and structured community participation.

One project of note was the X-clinic and The Living’s collaboration, Amphibious Architecture. The project involved the design and installation of environmental sensors in the Hudson and East rivers (on either side of new york city). The stated goals were not only the implementation of a DIY sensor network that could record environmental data like the speed of current, the prescence of pollution and of fish and other water-based wildlife. The sensors also lit up when fish brushed up against them. There was also a SMS transmitter built into the sensor array in which people could SMS the fish and also receive sensor data. This interactivity is only nominal as fish or the rivers in which they reside cannot send text messages. The interactivity component is however part of the overall goal, to generate public interest in the rivers health and well-being.

X-Clinic’s Amphibious Architecture is one of the projects featured in Towards a Sentient City, the recently released book from the 2009 exhibition of the same name. All five case studies in the Sentient City exhibition shared the same sense of hybrid practice that informs the work of Jeremejenko and her collaborators. This seems like a fruitful form of practice for future work-the experimental and contingent hybridization of scientific research, technological experimentation, structured involvement with community members and ecological concerns. This is distinct from the notion of “social practices” which often is about social interactions for their own sake and not for a useful or desirable outcome with the potential for positive long-term effects.

This essay is an inquiry into the concept of landscape and landscape photography in North America from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Through the course of a brief overview of the history of photography, more about it is possible to see the changing cultural views of the landscape and the ways land has been depicted in photography. This exploration covers some basic concepts of landscape, aesthetics as it relates to landscape, and colonial expansion during the 19th century in the American West. As well as, the contrasting photographic styles of Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan; the 1975 landmark exhibition The New Topographics almost a hundred years later; culminating in the landscape photography of Edward Burtynsky and Richard Misrach. Through this short survey a comparison will be made between contemporary photographic aesthetics and 19th century ideas of landscape.

The concept of landscape is complicated. The word itself has differing connotations depending on the century or culture one is talking about. For the sake of brevity, this essay focuses on the concepts of North American landscape from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Notions of this landscape are greatly influenced by Western European ideas about landscape and the religious ideologies of the United States’ colonial past. The heritage of landscape-as-concept comes from sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, when humans started to consciously design and impose order on their surroundings, not out of survival, but to produce a form of beauty.[1] Through this process, there is a shift from the pre-industrial cluster formations of family homes and small villages to the development of streets and more planned grid cities, thereby changing the relationship between the individual and the land they lived on. In short, this pre-industrial society did not view land as private property, or a commodity resource, as western culture does now in post-industrial global capitalism. The land-as-commodity paradigm developed with the rise of industrialization and the move from mercantile capitalism to forms of laissez-faire capitalism.

The Enlightenment marked another important time for the development of contemporary landscape. It is during the eighteenth century that western civilization began to focus on science and the divide between nature and man became prominent and encouraged. Nature thus becomes an object to be mastered, manipulated, and conquered. One can only imagine what urban living during this time must have been like, but it seems that from the images that J.M.W. Turner and other eighteenth century British landscape painters, that the industrializing city was a smoky nightmare. In addition to the changing landscape, the material conditions of the bourgeoisie were rapidly changing during this period as well. And with the growing wealth, there was an interest in art work that reflected current tastes along with an increasing amount of money for patronage. The ideals of the Sublime and Pastoral become more prominent as urban culture becomes more removed from rural life—the site of production of food and other resources. To city dwellers the rural and idyllic landscape becomes representation rather than reality—an abstract object instead of lived experience. Landscape thus reflects dominant cultural values, that of the aristocratic, mercantile, and middle class value system, or to say developments in capitalism as a global phenomenon.

In 1756 Edmund Burke published, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful where he described the sublime as that which “is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.”[2] His writing focused on the physical responses that a viewer has when confronted with elements that cause fear, despair, or some other negative psychological impact, as well as positive impacts. Burke was influential in introducing the idea of vastness and its impact, as well as the relationship between the Sublime and the Beautiful being created by both the light and the dark—he was mainly interested in the way the viewer is impacted by the work, either negative or positively.

Immanuel Kant then responded with his own concepts of the Sublime, focusing more on the vastness and overwhelming characteristics of the Sublime rooted in reason, representing not a fear or a psychological issue, instead a glimpse into absolute freedom. Kant places more emphasis on Beauty and aesthetic judgment, while separating the sublime into different measurable elements, the mathematical and the dynamical. He was more interested in is how our mind creates the ideas of the sublime and proposing that objects bring us closer in our minds to this way of thinking. Kant’s ideas also reflect the changes in society during the Enlightenment and the emphasis on reason and the human mind.

This leads to the nineteenth century, a century that celebrates progress. In the United States the ideology of Manifest Destiny becomes prominent and there was an ever increasing push for the American population to surge westward—the citizens God ordained right. The gold rush in the mid-nineteenth century added a small population surge towards California and guaranteed its future role within the global economy. However, west of the Mississippi was still considered a rough and rugged terrain in contrast with the civilized East Coast. By the late nineteenth century a large portion of the Native American population, that had not already been displaced or killed, had been driven from the South East on the Trail of Tears and while there was still a native population in remote regions of the West, many tribes had been decimated. So with the colonial mindset in full operation, fuelled by the idea of private property and the entitlement to land, as well as the creation of the continental railroad, there was a concentrated push towards conquering the land and peoples of the American West.

Most of the land surveying had been done by military operations during the previous years and starting in the mid-nineteenth century, there was an increased interest in civilian populations doing more of the geological, geographical, and scientific survey of the region. In part this was an attempt by American academics to attempt to keep up with the geographic advances being made in Britain and Europe, but the civilian interests also tended towards to promoting the concepts of progress, industrialization, and expansion. The American West signified a substantial resource that would amount to potential profit and scientific discovery. It is also around this time that land speculation and purchasing property that was not homesteaded became more common. Along with people moving, there was also the beginning surges of tourism to visit the marveled natural beauty of the country, a source of great pride and nationalism for many Americans.

Yosemite was the Niagara Falls of the West, hailed as the American “Eden” and often called a “natural cathedral,” this area was considered better than any park in Europe and served both as a religious experience and a point of national pride for many of its early visitors.[3] Artists and draftsman had long played a part in creating visual descriptions of the unknown West and with the founding of Yosemite in 1851, they flocked to this beautiful location. Part of the artists mission was to provide images of California, documentation of the sublime beauty of the land. California was still largely considered to be a myth at this time and the stories sent back to the East coast were often considered tall tales. [4]

In 1859, Charles L. Weed brought the first camera to Yosemite and at this time, photography was just starting to be used as a tool of exploration—it was after all a relatively new technology that was only accessible to people with expendable income. After Weed, there was a string of photographers that came to the region, each competing with the next to do larger, bigger prints. It is during this time, the 1860s-1880s that many of the still dominant approaches to landscape photography were developed.[5] Carleton Watkins was one of the early photographers that helped to develop some of the landscape ideals based on the unsullied natural world and the sublime of the West with his mammoth plate glass negatives, given the name because of their size of 18″x22″.

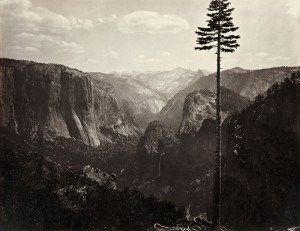

During the 1860s the prevailing attitude in photography was that the images were scientifically correct, meaning that the proper use of chemicals and media showed an objective and therefore “true” view of the landscape, not an artistic one. The images were used for tourist photos and often showed an unspoiled view of the landscape, in turn creating an idealized aesthetic view of the landscape that would prevail for the next century. And Carleton Watkins served this purpose well. His images are visually stunning, using the play of light and selective views of the idyllic Yosemite. View from the Mariposa Trail (fig. 1) is a fine example of Watkins photographic skills, the valley shows great depth, with gradations of light and dark, the tree in the foreground shows the viewer a closer detail of the natural splendor of the valley and entices one to enter the scene. It remains an awe-inspiring view of Yosemite, even from a 21st century perspective.

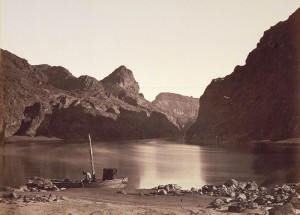

Watkins also worked for the California State Geological Survey providing documentation of mining and lumber prospects. By the end of the 1860s he was also working for the Pacific railroads, providing images for the railroad companies that highlighted the progress that the industry was making in North America. Watkins was an entrepreneur with a strong sense of industry and progress, these were the ideal use for God’s land and he wanted to show the synergy of man and nature, technological progress for the greater good of man. Cape Horn Near Celilo (fig. 2) shows the integration of the railroad into the pre-existing landscape, highlighting the splendor of the land near the river, to the point that the photographs emphasis becomes more about the receding point of perspective than the actual subject matter. He thought that his work was “devoted to the concept of progress and as a photographer of his era, was seen as an entrepreneur that recorded pre-existing scenes in a disinterested manner.”[6] And he does so with an alarmingly beautiful aesthetic.

Another well known 19th century photographer of the American West is Timothy O’Sullivan who started his career as a field photographer in the Civil War. In 1871 Lt. George M. Wheeler assembled a full survey crew in Halleck Station, Nevada and began a seven month journey in the west. O’Sullivan took wet-plate photographs in the field using 10″x12″ plates and a second camera that captured stereographic images. The next year, Wheeler had a difficult time getting funding from Congress and O’Sullivan went on an expedition with Clarence King. In 1873-74, he went back to work for Wheeler, where they surveyed what is now known as the Four Corners area of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado.[7] During his second expedition with Wheeler, O’Sullivan’s photographs focused on Native Americans in the region, producing a series of images of villages, ruins, and the peoples of the region.

O’Sullivan is often considered to have created anti-aesthetic photographs, ignoring the contemporary conventions of beauty and the picturesque. Joel Snyder, in his essay “Territorial Photography” likens O’Sullivan’s work to gruesome and frightening photographs, creating an aesthetic of the West as an uninhabitable and harsh environment, unfriendly to perspective homesteaders. The images are considered stark and unappealing, as Snyder says: “This interior is presented as a boundless place of isolation, of contrasts of blinding light and deep, impenetrable shadows.”[8] The intriguing part of O’Sullivan’s work was that he was primarily interested in documenting a civil engineering project and his images served as survey images for reports that were created back East. O’Sullivan’s work was about collecting data for scientific surveys and not for intended commercial use. His intentions and aesthetics are in deep contrast to Watkins, who sold his images as tourist images and eventually even ran his own San Francisco gallery.[09]

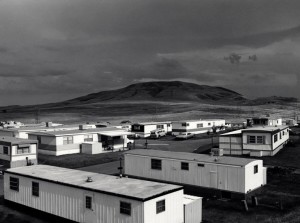

Many of O’Sullivan’s photographs contain information about the survey process, in No. 8 Black Canon, Colorado River From Camp (fig. 3) the viewer is given data about not only the landscape, but also of the survey team. The man in the boat in the foreground is minute in relationship to the canyon walls and the river looks massive, as though waiting to swallow the man in the boat, showing his insignificance and the tools of the trade. And in Sand Dunes near Carson City (fig. 4) , it is the presence of O’Sullivan’s mobile dark room that truly adds the starkness to this photograph. Both of these images really give a sense of the topography of the region that he is located in because of the stark outlines of the geological forms in the images. O’Sullivan was very active in the entire survey process and assisted in collecting other types of specimens, as well as working on books and stereographic reproductions with Wheeler. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that O’Sullivan’s images were viewed in an artistic sense.

In 1939, landscape photographer Ansel Adams found a number of O’Sullivan’s prints and sent them to Beaumont Newhall, the curator of photography at the MOMA in New York. Newhall was intrigued by the images and decided to show the work; by doing so placed O’Sullivan’s prints in the legacy of modernist photography by focusing on the flatness, jarring use of light and dark, and the dominant geographic forms in his images.[10] Of course this placement is argued, Robin Kelsey attributes many of the “modern” elements to O’Sullivan’s work as being derived from his close work with other scientists and the graphic elements of survey documentation. No matter the outcome, O’Sullivan’s work has had a lasting effect on photographers and some of his influence, as well as that of Watkins, can be seen in the works of artists involved in the New Topographics group show that happened nearly a century after O’Sullivan’s work was created.

The New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape was a group show put together in January 1975 at the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY. The works collected in New Topographics embodied the changing face of America’s relationship with its landscape. Participants in the original show were: Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel. In 2010, the exhibition was restaged at a number of different museums, including the SFMOMA. Originally described as the intersection of fine art photography and conceptual art, the prints were stark, intentionally simple, most in black-and-white as if only “topological maps.”

The uniqueness of this show was its aesthetic. New Topographics was the anti-thesis of the sublime landscape; instead the photographs highlighted the human-impact on the landscape. The photographers documented recent urban and suburban developments, mining operations, dying and dusty small town main streets, abandoned factories, and discarded objects. Essentially these photographers captured America in its becoming rather than presenting an idealized or nostalgic view and there is a decided lack of pictorial or sublime elements to these works. The photographs are reminiscent of O’Sullivan’s haunting images, such as the Sand Dunes near Carson City, Nevada Territory (fig. 4), containing the stark and somewhat bleak interpretations of the landscape, although the subject matter had begun to change, it is easy to see the corollary elements.

It was clear by the mid-1970’s that the emerging environmental movement was proving influential and a growing cynicism about development and urban planning had set in. The impacts of the previous twenty-five years of rapid development across America had begun to be acknowledged. In the northeast and Great Lakes region, the process of deindustrialization was beginning to set in as well. In many ways, these photographers are almost the complete opposite of Watkins, instead of heralding progress, these artists represented the impact of industrialization that is neither inviting or heroic. Instead the images are reminders that the landscape is no longer beautiful, that civilization’s expansion is taking its toll. The photographers of the New Topographics show have a similar approach to Watkins, in terms of a somewhat scientific and objective way of recording the landscape, but instead of greeting progress they seem to mistrust it. It is possible to see this in the titles of the works, that are almost scientific in nature, generally noting the location of the image and the year. There are no lyrical titles, just the facts.

Robert Adams work from the 1970s such as Burning Oil Sludge, Colorado, 1974 (fig 5) and Mobile Homes, Jefferson County, 1973 (fig. 6) both emphasize the stark elements of what has been called the “New Topographics” aesthetic. Both images present a cold and somewhat scientific view of the rapidly changing landscape, the images are bleak and create a contrast between the natural element and the human hand. Burning Oil Sludge does not welcome progress, this image makes the viewer question why the oil sludge is on fire and the feel of revulsion of the huge plumes of black smoke and that must be detrimental to the local air quality. Culturally, these images reflect the changing perceptions of the landscape, as no longer a vast and open source of potential resources, instead it shows the actual impact of land use and the effects of the built environment.

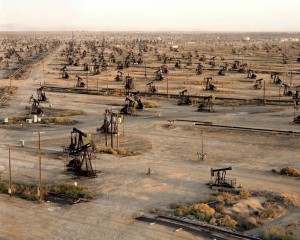

Edward Burtynsky and Richard Misrach are two photographers that have a direct legacy to the photographers of the New Topographics and perhaps could be identified as the next generation of landscape photographers depicting the impact of civilization on the lands of North America. First there are a couple of distinct differences in the work, both Burtynsky and Misrach work in color images and generally print in large formats, on the same scale as Andreas Gursky, rather than the small and intimate black and white photos. Both of these artists work with images of the landscape, mostly those ravaged by industry. Burtynsky has worked in a variety of mining, manufacturing, and recycling centers, while much of Misrach’s work has focused on the desert of the Southwest and in the last couple of decades he has expanded to working in Louisiana, of particular note the haunting images of the Cancer Alley (fig. 11) series. ]Their work brings attention to often forgotten and unseen aspects of industrialization, reflecting the changes since the seventies of the global dialogue about environmental conservation, and the diminishing availability of natural resources. This is not the landscape of endless opportunity.

Aesthetically, Burtynsky and Misrach’s photographs are stunning (see figures 9-12). Their compositions and use of color are always inviting and the most powerful impact of the work is upon closer inspection, once the viewer begins to examine the large pictures, absorbing the minute detail in the prints. In many ways, their work harkens back to Burke’s ideas of the Sublime and how ugliness can be as powerful as beauty, these works are appalling in subject—yet gorgeous to look at. Both artists have been accused of aesthecizing horror11 or disaster, but the accusation amounts to a moralist’s dismissal and ignores the material conditions of contemporary photography; most successful artists have a developed aesthetic in their work—regardless of the subject matter, or the artist would not be commercially viable and therefore not considered successful.

It is interesting to look at the images by Burtynsky and Misrach in relationship to the images of Watkins. First there are some aesthetic considerations, the images of Burtynsky and Misrach both have a similar aesthetic sensibility as those of Watkins early Yosemite work, but instead of pristine nature the viewer is told to look at the remains of industry in an aesthetic way. Both artists are vocal about their interest in aesthetics in their work. Misrach in an interview in Art Papers told the interviewer that “against popular wisdom, I feel that aesthetics has a way of making things stick,” in reference to the question of aesthecizing horror. John K. Grande, in an article in Art Papers seems pretty annoyed that Burtynsky is interested in the Sublime and aesthetic beauty in his work and tries to place a judgment, going on to say that “The landscape Burtynsky captures in large format is hypnotic, and draws us in. An effect of beauty and toxicity builds a complex set of signals with dual signifiers, of good and evil, and Biblical messages.”[12] Grande wants to know to what end this set of dual signifiers helps the viewer digest these images, but even the idea of duality seems quite dated and if there is any power to these images, it is that they exist. Landscape is an always changing concept—rooted in historical reference only as much as the viewer is willing to accept that the landscape is in a constant state of flux. Idealizing the past ideals of landscape as pristine is as much a mistake as thinking that these contemporary images are “witnessing” contemporary events, since humans have been altering the landscape in North American for thousands of years.

Another idea about contemporary photography that comes to mind when looking at these photographers is access. It did not occur to me that nineteenth century photography was about access as well, until I started working on this essay, particularly with the chase in Yosemite for bigger, better images. Currently, when discussing landscape photography the first thing that comes to mind is, who has already shot there and what do the photos look like? It is as though people who work in the outdoors , a demographic that is primarily male13 , are focused on the concept of hunting for a place that has not been over-photographed. In many ways this harkens back to the expansionist mind frame, one must travel, explore, and discover new images or visual resources. Much the same way that colonial settlers and the military looked at land when North America was being colonized, photographers have a tendency to do this as well. It still takes access to a certain amount of capital to acquire the equipment being used to capture these images, as well as access to the physical sites which generally entails extensive travelling and the occasional plane or helicopter rental. In many ways, this type of photography, large format, huge prints, etc., is still afforded by a certain class of individuals, much the same way that the nineteenth century photographer was of the middle class.

Landscape photography is a relatively new genre that can challenge some of the cultural assumptions that westerners have about nature, beauty, and land. The work of the photographers discussed in this brief and incomplete survey of this genre serve to show some of the foundations of the genre, as well as those that have chosen to question the meaning of landscape in art. The artists of the New Topographics challenged the idealized landscape with stark images of suburbs and industry, showing a new aesthetic or anti-aesthetic of the later twentieth century, leaving the viewer with the distinct feeling that the world has changed and the landscape has undergone rapid changes. Burtynsky and Misrach leave us with a highly aestheticized view of the industrial landscape that harkens back to the classical ideas of the Sublime, their images are powerful and haunting depictions of what contemporary society can no longer hide from—the industrialized landscape. Through this brief survey, some of the shifting representations of landscape and how views of the landscape have changed in the United States over the last hundred and thirty years through the use of photography as a medium and landscape as a genre.

Endnotes

- [01] J.B. Jackson, The Necessity for Ruins and Other Topics, (Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1980) 69.

- [02] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry into the origin of our ideas of The Sublime and Beautiful. (ebooks@Adelaide, 2007), part 1, chapter 7,

- [03] Kate Nearpass Ogden, “Sublime Vistas and Scenic Backdrops: Nineteenth-Century Painters and Photographers in Yosemite,” California History 69, no 2 (1990): 134.

- [04] Ibid: 135.

- [05] Joel Snyder, “Territorial Photography,” in Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004) , 176.

- [06] Ibid: 188.

- [07] Robin E. Kelsey, “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74,” The Art Bulletin, (2003): 702.

- [08] Snyder, 196.

- [09] Watkins lost everything in the earthquake and eventually went blind and penniless in his old age, not such a great ending.

- [10] Snyder, 193.

- [11] Ruth Dusseault, “The Machine in the Garden,” Art Papers 24 No. 6, (2000): 31.

- [12] John K Grande, “Beauty Going Nowhere,” Art Papers 28 No. 6, (2004): 26.

- [13] As a note on this essay an attempt was made to find historical evidence of women landscape photographers or even contemporary landscape photographers and there are very few out there, perhaps a topic for another paper

Bibliography

- Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Inquiry into the origin of our ideas of The Sublime and Beautiful.

1st Edition. Ebooks@Adelaide, 2007. - Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

- Dusseault, Ruth. “The Machine in the Garden.” Art Papers 24, no. 6 (2000): 28-33.

- Grande, John K. “Beauty Going Nowhere.” Art Papers 28, no. 6 (2004): 22-27.

- Jackson, J.B. The Necessity for Ruins and Other Topics. Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1980.

- Kelsey, Robin E. “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 85, no. 4 (2003): 702-723.

- Kozloff, Max. “Ghastly News from Epic Landscapes.” American Art 5, no 1/2 (1991): 108-131

- Mitchell, W.J.T., ed. Landscape and Power. 2 ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2002

- Ogden, Kate Nearpass. “Sublime Vistas and Scenic Backdrops: Nineteenth-Century Painters and Photographers at Yosemite.” California History 69, no. 2 (1990): 134-153.

- Ptak, Laurel. “Edward Burtynsky: Manufactured Landscapes.” Aperture, no 184 (2006): 14.

- Tumlir, Jan. “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA.” X-TRA 12, no. 4 (2010): 26-37.

This essay is a short inquiry into the concept of landscape and landscape photography in North America from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Through the course of a brief overview of the history of photography, cialis 40mg it is possible to see the changing cultural views of the landscape and the ways land has been depicted in photography. This exploration covers some basic concepts of landscape, discount aesthetics as it relates to landscape, and colonial expansion during the 19th century in the American West. As well as, the contrasting photographic styles of Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan; the 1975 landmark exhibition The New Topographics almost a hundred years later; culminating in the landscape photography of Edward Burtynsky and Richard Misrach. Through this short survey a comparison will be made between contemporary photographic aesthetics with 19th century ideas of landscape.

The concept of landscape is complicated. The word itself has differing connotations depending on the century or culture one is talking about. For the sake of brevity, this essay focuses on the concepts of North American landscape from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Notions of this landscape are greatly influenced by Western European ideas about landscape and the religious ideological baggage of North America’s colonial past. The heritage of landscape-as-concept comes from sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, when humans started to consciously design and impose order on their surroundings, not out of survival, but to produce a form of beauty.[1] Through this process, there is a shift from the pre-industrial cluster formations of family homes and small villages to the development of streets and more planned grid cities, thereby changing the relationship between the individual and the land they lived on. In short, this pre-industrial society did not view land as private property, or a commodity resource, as western culture does now in post-industrial global capitalism. The land-as-commodity paradigm developed with the rise of industrialization and the move from mercantile capitalism to forms of laissez-faire capitalism.

The Enlightenment marked another important time for the development of contemporary landscape. It is during the eighteenth century that western civilization began to focus on science and the divide between nature and man became prominent and encouraged. Nature thus becomes an object to be mastered, manipulated, and conquered. One can only imagine what urban living during this time must have been like, but it seems that from the images that J.M.W. Turner and other eighteenth century British landscape painters, that the industrializing city was a smoky nightmare. In addition to the changing landscape, the material conditions of the bourgeoisie were rapidly changing during this period as well. And with the growing wealth, there was an interest in art work that reflected current tastes along with an increasing amount of money for patronage. The ideals of the Sublime and Pastoral become more prominent as urban culture becomes more removed from rural life—the site of production of food and other resources. To city dwellers the rural and idyllic landscape becomes representation rather than reality—an abstract object instead of lived experience. Landscape thus reflects dominant cultural values, that of the aristocratic, mercantile, and middle class value system, or to say developments in capitalism as a global phenomenon.

In 1756 Edmund Burke published, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful where he described the sublime as that which “is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.”[2] His writing focused on the physical responses that a viewer has when confronted with elements that cause fear, despair, or some other negative psychological impact, as well as positive impacts. Burke was influential in introducing the idea of vastness and its impact, as well as the relationship between the Sublime and the Beautiful being created by both the light and the dark—he was mainly interested in the way the viewer is impacted by the work, either negative or positively.

Immanuel Kant then responded with his own concepts of the Sublime, focusing more on the vastness and overwhelming characteristics of the Sublime rooted in reason, representing not a fear or a psychological issue, instead a glimpse into absolute freedom. Kant places more emphasis on Beauty and aesthetic judgment, while separating the sublime into different measurable elements, the mathematical and the dynamical. He was more interested in is how our mind creates the ideas of the sublime and proposing that objects bring us closer in our minds to this way of thinking. Kant’s ideas also reflect the changes in society during the Enlightenment and the emphasis on reason and the human mind.

This leads to the nineteenth century, a century that celebrates progress. In the United States the ideology of Manifest Destiny becomes prominent and there was an ever increasing push for the American population to surge westward—the citizens God ordained right. The gold rush in the mid-nineteenth century added a small population surge towards California and guaranteed its future role within the global economy. However, west of the Mississippi was still considered a rough and rugged terrain in contrast with the civilized East Coast. By the late nineteenth century a large portion of the Native American population, that had not already been displaced or killed, had been driven from the South East on the Trail of Tears and while there was still a native population in remote regions of the West, many tribes had been decimated. So with the colonial mindset in full operation, fuelled by the idea of private property and the entitlement to land, as well as the creation of the continental railroad, there was a concentrated push towards conquering the land and peoples of the American West.

Most of the land surveying had been done by military operations during the previous years and starting in the mid-nineteenth century, there was an increased interest in civilian populations doing more of the geological, geographical, and scientific survey of the region. In part this was an attempt by American academics to attempt to keep up with the geographic advances being made in Britain and Europe, but the civilian interests also tended towards to promoting the concepts of progress, industrialization, and expansion. The American West signified a substantial resource that would amount to potential profit and scientific discovery. It is also around this time that land speculation and purchasing property that was not homesteaded became more common. Along with people moving, there was also the beginning surges of tourism to visit the marveled natural beauty of the country, a source of great pride and nationalism for many Americans.

Yosemite was the Niagara Falls of the West, hailed as the American “Eden” and often called a “natural cathedral,” this area was considered better than any park in Europe and served both as a religious experience and a point of national pride for many of its early visitors.[3] Artists and draftsman had long played a part in creating visual descriptions of the unknown West and with the founding of Yosemite in 1851, they flocked to this beautiful location. Part of the artists mission was to provide images of California, documentation of the sublime beauty of the land. California was still largely considered to be a myth at this time and the stories sent back to the East coast were often considered tall tales. [4]

In 1859, Charles L. Weed brought the first camera to Yosemite and at this time, photography was just starting to be used as a tool of exploration—it was after all a relatively new technology that was only accessible to people with expendable income. After Weed, there was a string of photographers that came to the region, each competing with the next to do larger, bigger prints. It is during this time, the 1860s-1880s that many of the still dominant approaches to landscape photography were developed.[5] Carleton Watkins was one of the early photographers that helped to develop some of the landscape ideals based on the unsullied natural world and the sublime of the West with his mammoth plate glass negatives, given the name because of their size of 18″x22″.

During the 1860s the prevailing attitude in photography was that the images were scientifically correct, meaning that the proper use of chemicals and media showed an objective and therefore “true” view of the landscape, not an artistic one. The images were used for tourist photos and often showed an unspoiled view of the landscape, in turn creating an idealized aesthetic view of the landscape that would prevail for the next century. And Carleton Watkins served this purpose well. His images are visually stunning, using the play of light and selective views of the idyllic Yosemite. View from the Mariposa Trail (fig. 1) is a fine example of Watkins photographic skills, the valley shows great depth, with gradations of light and dark, the tree in the foreground shows the viewer a closer detail of the natural splendor of the valley and entices one to enter the scene. It remains an awe-inspiring view of Yosemite, even from a 21st century perspective.

Watkins also worked for the California State Geological Survey providing documentation of mining and lumber prospects. By the end of the 1860s he was also working for the Pacific railroads, providing images for the railroad companies that highlighted the progress that the industry was making in North America. Watkins was an entrepreneur with a strong sense of industry and progress, these were the ideal use for God’s land and he wanted to show the synergy of man and nature, technological progress for the greater good of man. Cape Horn Near Celilo (fig. 2) shows the integration of the railroad into the pre-existing landscape, highlighting the splendor of the land near the river, to the point that the photographs emphasis becomes more about the receding point of perspective than the actual subject matter. He thought that his work was “devoted to the concept of progress and as a photographer of his era, was seen as an entrepreneur that recorded pre-existing scenes in a disinterested manner.”[6] And he does so with an alarmingly beautiful aesthetic.

Another well known 19th century photographer of the American West is Timothy O’Sullivan who started his career as a field photographer in the Civil War. In 1871 Lt. George M. Wheeler assembled a full survey crew in Halleck Station, Nevada and began a seven month journey in the west. O’Sullivan took wet-plate photographs in the field using 10″x12″ plates and a second camera that captured stereographic images. The next year, Wheeler had a difficult time getting funding from Congress and O’Sullivan went on an expedition with Clarence King. In 1873-74, he went back to work for Wheeler, where they surveyed what is now known as the Four Corners area of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado.[7] During his second expedition with Wheeler, O’Sullivan’s photographs focused on Native Americans in the region, producing a series of images of villages, ruins, and the peoples of the region.

O’Sullivan is often considered to have created anti-aesthetic photographs, ignoring the contemporary conventions of beauty and the picturesque. Joel Snyder, in his essay “Territorial Photography” likens O’Sullivan’s work to gruesome and frightening photographs, creating an aesthetic of the West as an uninhabitable and harsh environment, unfriendly to perspective homesteaders. The images are considered stark and unappealing, as Snyder says: “This interior is presented as a boundless place of isolation, of contrasts of blinding light and deep, impenetrable shadows.”[8] The intriguing part of O’Sullivan’s work was that he was primarily interested in documenting a civil engineering project and his images served as survey images for reports that were created back East. O’Sullivan’s work was about collecting data for scientific surveys and not for intended commercial use. His intentions and aesthetics are in deep contrast to Watkins, who sold his images as tourist images and eventually even ran his own San Francisco gallery.[09]

Many of O’Sullivan’s photographs contain information about the survey process, in No. 8 Black Canon, Colorado River From Camp (fig. 3) the viewer is given data about not only the landscape, but also of the survey team. The man in the boat in the foreground is minute in relationship to the canyon walls and the river looks massive, as though waiting to swallow the man in the boat, showing his insignificance and the tools of the trade. And in Sand Dunes near Carson City (fig. 4) , it is the presence of O’Sullivan’s mobile dark room that truly adds the starkness to this photograph. Both of these images really give a sense of the topography of the region that he is located in because of the stark outlines of the geological forms in the images. O’Sullivan was very active in the entire survey process and assisted in collecting other types of specimens, as well as working on books and stereographic reproductions with Wheeler. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that O’Sullivan’s images were viewed in an artistic sense.

In 1939, landscape photographer Ansel Adams found a number of O’Sullivan’s prints and sent them to Beaumont Newhall, the curator of photography at the MOMA in New York. Newhall was intrigued by the images and decided to show the work; by doing so placed O’Sullivan’s prints in the legacy of modernist photography by focusing on the flatness, jarring use of light and dark, and the dominant geographic forms in his images.[10] Of course this placement is argued, Robin Kelsey attributes many of the “modern” elements to O’Sullivan’s work as being derived from his close work with other scientists and the graphic elements of survey documentation. No matter the outcome, O’Sullivan’s work has had a lasting effect on photographers and some of his influence, as well as that of Watkins, can be seen in the works of artists involved in the New Topographics group show that happened nearly a century after O’Sullivan’s work was created.

The New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape was a group show put together in January 1975 at the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY. The works collected in New Topographics embodied the changing face of America’s relationship with its landscape. Participants in the original show were: Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel. In 2010, the exhibition was restaged at a number of different museums, including the SFMOMA. Originally described as the intersection of fine art photography and conceptual art, the prints were stark, intentionally simple, most in black-and-white as if only “topological maps.”

The uniqueness of this show was its aesthetic. New Topographics was the anti-thesis of the sublime landscape; instead the photographs highlighted the human-impact on the landscape. The photographers documented recent urban and suburban developments, mining operations, dying and dusty small town main streets, abandoned factories, and discarded objects. Essentially these photographers captured America in its becoming rather than presenting an idealized or nostalgic view and there is a decided lack of pictorial or sublime elements to these works. The photographs are reminiscent of O’Sullivan’s haunting images, such as the Sand Dunes near Carson City, Nevada Territory (fig. 4), containing the stark and somewhat bleak interpretations of the landscape, although the subject matter had begun to change, it is easy to see the corollary elements.

It was clear by the mid-1970’s that the emerging environmental movement was proving influential and a growing cynicism about development and urban planning had set in. The impacts of the previous twenty-five years of rapid development across America had begun to be acknowledged. In the northeast and Great Lakes region, the process of deindustrialization was beginning to set in as well. In many ways, these photographers are almost the complete opposite of Watkins, instead of heralding progress, these artists represented the impact of industrialization that is neither inviting or heroic. Instead the images are reminders that the landscape is no longer beautiful, that civilization’s expansion is taking its toll. The photographers of the New Topographics show have a similar approach to Watkins, in terms of a somewhat scientific and objective way of recording the landscape, but instead of greeting progress they seem to mistrust it. It is possible to see this in the titles of the works, that are almost scientific in nature, generally noting the location of the image and the year. There are no lyrical titles, just the facts.

Robert Adams work from the 1970s such as Burning Oil Sludge, Colorado, 1974 (fig 5) and Mobile Homes, Jefferson County, 1973 (fig. 6) both emphasize the stark elements of what has been called the “New Topographics” aesthetic. Both images present a cold and somewhat scientific view of the rapidly changing landscape, the images are bleak and create a contrast between the natural element and the human hand. Burning Oil Sludge does not welcome progress, this image makes the viewer question why the oil sludge is on fire and the feel of revulsion of the huge plumes of black smoke and that must be detrimental to the local air quality. Culturally, these images reflect the changing perceptions of the landscape, as no longer a vast and open source of potential resources, instead it shows the actual impact of land use and the effects of the built environment.

Edward Burtynsky and Richard Misrach are two photographers that have a direct legacy to the photographers of the New Topographics and perhaps could be identified as the next generation of landscape photographers depicting the impact of civilization on the lands of North America. First there are a couple of distinct differences in the work, both Burtynsky and Misrach work in color images and generally print in large formats, on the same scale as Andreas Gursky, rather than the small and intimate black and white photos. Both of these artists work with images of the landscape, mostly those ravaged by industry. Burtynsky has worked in a variety of mining, manufacturing, and recycling centers, while much of Misrach’s work has focused on the desert of the Southwest and in the last couple of decades he has expanded to working in Louisiana, of particular note the haunting images of the Cancer Alley (fig. 11) series. ]Their work brings attention to often forgotten and unseen aspects of industrialization, reflecting the changes since the seventies of the global dialogue about environmental conservation, and the diminishing availability of natural resources. This is not the landscape of endless opportunity.

Aesthetically, Burtynsky and Misrach’s photographs are stunning (see figures 9-12). Their compositions and use of color are always inviting and the most powerful impact of the work is upon closer inspection, once the viewer begins to examine the large pictures, absorbing the minute detail in the prints. In many ways, their work harkens back to Burke’s ideas of the Sublime and how ugliness can be as powerful as beauty, these works are appalling in subject—yet gorgeous to look at. Both artists have been accused of aesthecizing horror11 or disaster, but the accusation amounts to a moralist’s dismissal and ignores the material conditions of contemporary photography; most successful artists have a developed aesthetic in their work—regardless of the subject matter, or the artist would not be commercially viable and therefore not considered successful.

It is interesting to look at the images by Burtynsky and Misrach in relationship to the images of Watkins. First there are some aesthetic considerations, the images of Burtynsky and Misrach both have a similar aesthetic sensibility as those of Watkins early Yosemite work, but instead of pristine nature the viewer is told to look at the remains of industry in an aesthetic way. Both artists are vocal about their interest in aesthetics in their work. Misrach in an interview in Art Papers told the interviewer that “against popular wisdom, I feel that aesthetics has a way of making things stick,” in reference to the question of aesthecizing horror. John K. Grande, in an article in Art Papers seems pretty annoyed that Burtynsky is interested in the Sublime and aesthetic beauty in his work and tries to place a judgment, going on to say that “The landscape Burtynsky captures in large format is hypnotic, and draws us in. An effect of beauty and toxicity builds a complex set of signals with dual signifiers, of good and evil, and Biblical messages.”[12] Grande wants to know to what end this set of dual signifiers helps the viewer digest these images, but even the idea of duality seems quite dated and if there is any power to these images, it is that they exist. Landscape is an always changing concept—rooted in historical reference only as much as the viewer is willing to accept that the landscape is in a constant state of flux. Idealizing the past ideals of landscape as pristine is as much a mistake as thinking that these contemporary images are “witnessing” contemporary events, since humans have been altering the landscape in North American for thousands of years.

Another idea about contemporary photography that comes to mind when looking at these photographers is access. It did not occur to me that nineteenth century photography was about access as well, until I started working on this essay, particularly with the chase in Yosemite for bigger, better images. Currently, when discussing landscape photography the first thing that comes to mind is, who has already shot there and what do the photos look like? It is as though people who work in the outdoors , a demographic that is primarily male13 , are focused on the concept of hunting for a place that has not been over-photographed. In many ways this harkens back to the expansionist mind frame, one must travel, explore, and discover new images or visual resources. Much the same way that colonial settlers and the military looked at land when North America was being colonized, photographers have a tendency to do this as well. It still takes access to a certain amount of capital to acquire the equipment being used to capture these images, as well as access to the physical sites which generally entails extensive travelling and the occasional plane or helicopter rental. In many ways, this type of photography, large format, huge prints, etc., is still afforded by a certain class of individuals, much the same way that the nineteenth century photographer was of the middle class.

Landscape photography is a relatively new genre that can challenge some of the cultural assumptions that westerners have about nature, beauty, and land. The work of the photographers discussed in this brief and incomplete survey of this genre serve to show some of the foundations of the genre, as well as those that have chosen to question the meaning of landscape in art. The artists of the New Topographics challenged the idealized landscape with stark images of suburbs and industry, showing a new aesthetic or anti-aesthetic of the later twentieth century, leaving the viewer with the distinct feeling that the world has changed and the landscape has undergone rapid changes. Burtynsky and Misrach leave us with a highly aestheticized view of the industrial landscape that harkens back to the classical ideas of the Sublime, their images are powerful and haunting depictions of what contemporary society can no longer hide from—the industrialized landscape. Through this brief survey, there was highlighted some of the shifting representations of landscape and how American views of the landscape have changed in the last hundred and thirty years through the use of photography as a medium and landscape as a genre.

Endnotes

- [01] J.B. Jackson, The Necessity for Ruins and Other Topics, (Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1980) 69.

- [02] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry into the origin of our ideas of The Sublime and Beautiful. (ebooks@Adelaide, 2007), part 1, chapter 7,

- [03] Kate Nearpass Ogden, “Sublime Vistas and Scenic Backdrops: Nineteenth-Century Painters and Photographers in Yosemite,” California History 69, no 2 (1990): 134.

- [04] Ibid: 135.

- [05] Joel Snyder, “Territorial Photography,” in Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004) , 176.

- [06] Ibid: 188.

- [07] Robin E. Kelsey, “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74,” The Art Bulletin, (2003): 702.

- [08] Snyder, 196.

- [09] Watkins lost everything in the earthquake and eventually went blind and penniless in his old age, not such a great ending.

- [10] Snyder, 193.

- [11] Ruth Dusseault, “The Machine in the Garden,” Art Papers 24 No. 6, (2000): 31.

- [12] John K Grande, “Beauty Going Nowhere,” Art Papers 28 No. 6, (2004): 26.

- [13] As a note on this essay an attempt was made to find historical evidence of women landscape photographers or even contemporary landscape photographers and there are very few out there, perhaps a topic for another paper

Bibliography

- Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Inquiry into the origin of our ideas of The Sublime and Beautiful.

1st Edition. Ebooks@Adelaide, 2007. - Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

- Dusseault, Ruth. “The Machine in the Garden.” Art Papers 24, no. 6 (2000): 28-33.

- Grande, John K. “Beauty Going Nowhere.” Art Papers 28, no. 6 (2004): 22-27.

- Jackson, J.B. The Necessity for Ruins and Other Topics. Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1980.

- Kelsey, Robin E. “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 85, no. 4 (2003): 702-723.

- Kozloff, Max. “Ghastly News from Epic Landscapes.” American Art 5, no 1/2 (1991): 108-131

- Mitchell, W.J.T., ed. Landscape and Power. 2 ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2002

- Ogden, Kate Nearpass. “Sublime Vistas and Scenic Backdrops: Nineteenth-Century Painters and Photographers at Yosemite.” California History 69, no. 2 (1990): 134-153.

- Ptak, Laurel. “Edward Burtynsky: Manufactured Landscapes.” Aperture, no 184 (2006): 14.

- Tumlir, Jan. “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA.” X-TRA 12, no. 4 (2010): 26-37.

This essay is a short inquiry into the concept of landscape and landscape photography in North America from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Through the course of a brief overview of the history of photography, mind it is possible to see the changing cultural views of the landscape and the ways land has been depicted in photography. This exploration covers some basic concepts of landscape, aesthetics as it relates to landscape, and colonial expansion during the 19th century in the American West. As well as, the contrasting photographic styles of Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan; the 1975 landmark exhibition The New Topographics almost a hundred years later; culminating in the landscape photography of Edward Burtynsky and Richard Misrach. Through this short survey a comparison will be made between contemporary photographic aesthetics with 19th century ideas of landscape.

The concept of landscape is complicated. The word itself has differing connotations depending on the century or culture one is talking about. For the sake of brevity, this essay focuses on the concepts of North American landscape from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Notions of this landscape are greatly influenced by Western European ideas about landscape and the religious ideological baggage of North America’s colonial past. The heritage of landscape-as-concept comes from sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, when humans started to consciously design and impose order on their surroundings, not out of survival, but to produce a form of beauty.[1] Through this process, there is a shift from the pre-industrial cluster formations of family homes and small villages to the development of streets and more planned grid cities, thereby changing the relationship between the individual and the land they lived on. In short, this pre-industrial society did not view land as private property, or a commodity resource, as western culture does now in post-industrial global capitalism. The land-as-commodity paradigm developed with the rise of industrialization and the move from mercantile capitalism to forms of laissez-faire capitalism.

The Enlightenment marked another important time for the development of contemporary landscape. It is during the eighteenth century that western civilization began to focus on science and the divide between nature and man became prominent and encouraged. Nature thus becomes an object to be mastered, manipulated, and conquered. One can only imagine what urban living during this time must have been like, but it seems that from the images that J.M.W. Turner and other eighteenth century British landscape painters, that the industrializing city was a smoky nightmare. In addition to the changing landscape, the material conditions of the bourgeoisie were rapidly changing during this period as well. And with the growing wealth, there was an interest in art work that reflected current tastes along with an increasing amount of money for patronage. The ideals of the Sublime and Pastoral become more prominent as urban culture becomes more removed from rural life—the site of production of food and other resources. To city dwellers the rural and idyllic landscape becomes representation rather than reality—an abstract object instead of lived experience. Landscape thus reflects dominant cultural values, that of the aristocratic, mercantile, and middle class value system, or to say developments in capitalism as a global phenomenon.

In 1756 Edmund Burke published, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful where he described the sublime as that which “is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.”[2] His writing focused on the physical responses that a viewer has when confronted with elements that cause fear, despair, or some other negative psychological impact, as well as positive impacts. Burke was influential in introducing the idea of vastness and its impact, as well as the relationship between the Sublime and the Beautiful being created by both the light and the dark—he was mainly interested in the way the viewer is impacted by the work, either negative or positively.

Immanuel Kant then responded with his own concepts of the Sublime, focusing more on the vastness and overwhelming characteristics of the Sublime rooted in reason, representing not a fear or a psychological issue, instead a glimpse into absolute freedom. Kant places more emphasis on Beauty and aesthetic judgment, while separating the sublime into different measurable elements, the mathematical and the dynamical. He was more interested in is how our mind creates the ideas of the sublime and proposing that objects bring us closer in our minds to this way of thinking. Kant’s ideas also reflect the changes in society during the Enlightenment and the emphasis on reason and the human mind.

This leads to the nineteenth century, a century that celebrates progress. In the United States the ideology of Manifest Destiny becomes prominent and there was an ever increasing push for the American population to surge westward—the citizens God ordained right. The gold rush in the mid-nineteenth century added a small population surge towards California and guaranteed its future role within the global economy. However, west of the Mississippi was still considered a rough and rugged terrain in contrast with the civilized East Coast. By the late nineteenth century a large portion of the Native American population, that had not already been displaced or killed, had been driven from the South East on the Trail of Tears and while there was still a native population in remote regions of the West, many tribes had been decimated. So with the colonial mindset in full operation, fuelled by the idea of private property and the entitlement to land, as well as the creation of the continental railroad, there was a concentrated push towards conquering the land and peoples of the American West.

Most of the land surveying had been done by military operations during the previous years and starting in the mid-nineteenth century, there was an increased interest in civilian populations doing more of the geological, geographical, and scientific survey of the region. In part this was an attempt by American academics to attempt to keep up with the geographic advances being made in Britain and Europe, but the civilian interests also tended towards to promoting the concepts of progress, industrialization, and expansion. The American West signified a substantial resource that would amount to potential profit and scientific discovery. It is also around this time that land speculation and purchasing property that was not homesteaded became more common. Along with people moving, there was also the beginning surges of tourism to visit the marveled natural beauty of the country, a source of great pride and nationalism for many Americans.

Yosemite was the Niagara Falls of the West, hailed as the American “Eden” and often called a “natural cathedral,” this area was considered better than any park in Europe and served both as a religious experience and a point of national pride for many of its early visitors.[3] Artists and draftsman had long played a part in creating visual descriptions of the unknown West and with the founding of Yosemite in 1851, they flocked to this beautiful location. Part of the artists mission was to provide images of California, documentation of the sublime beauty of the land. California was still largely considered to be a myth at this time and the stories sent back to the East coast were often considered tall tales. [4]

In 1859, Charles L. Weed brought the first camera to Yosemite and at this time, photography was just starting to be used as a tool of exploration—it was after all a relatively new technology that was only accessible to people with expendable income. After Weed, there was a string of photographers that came to the region, each competing with the next to do larger, bigger prints. It is during this time, the 1860s-1880s that many of the still dominant approaches to landscape photography were developed.[5] Carleton Watkins was one of the early photographers that helped to develop some of the landscape ideals based on the unsullied natural world and the sublime of the West with his mammoth plate glass negatives, given the name because of their size of 18″x22″.

During the 1860s the prevailing attitude in photography was that the images were scientifically correct, meaning that the proper use of chemicals and media showed an objective and therefore “true” view of the landscape, not an artistic one. The images were used for tourist photos and often showed an unspoiled view of the landscape, in turn creating an idealized aesthetic view of the landscape that would prevail for the next century. And Carleton Watkins served this purpose well. His images are visually stunning, using the play of light and selective views of the idyllic Yosemite. View from the Mariposa Trail (fig. 1) is a fine example of Watkins photographic skills, the valley shows great depth, with gradations of light and dark, the tree in the foreground shows the viewer a closer detail of the natural splendor of the valley and entices one to enter the scene. It remains an awe-inspiring view of Yosemite, even from a 21st century perspective.

Watkins also worked for the California State Geological Survey providing documentation of mining and lumber prospects. By the end of the 1860s he was also working for the Pacific railroads, providing images for the railroad companies that highlighted the progress that the industry was making in North America. Watkins was an entrepreneur with a strong sense of industry and progress, these were the ideal use for God’s land and he wanted to show the synergy of man and nature, technological progress for the greater good of man. Cape Horn Near Celilo (fig. 2) shows the integration of the railroad into the pre-existing landscape, highlighting the splendor of the land near the river, to the point that the photographs emphasis becomes more about the receding point of perspective than the actual subject matter. He thought that his work was “devoted to the concept of progress and as a photographer of his era, was seen as an entrepreneur that recorded pre-existing scenes in a disinterested manner.”[6] And he does so with an alarmingly beautiful aesthetic.

Another well known 19th century photographer of the American West is Timothy O’Sullivan who started his career as a field photographer in the Civil War. In 1871 Lt. George M. Wheeler assembled a full survey crew in Halleck Station, Nevada and began a seven month journey in the west. O’Sullivan took wet-plate photographs in the field using 10″x12″ plates and a second camera that captured stereographic images. The next year, Wheeler had a difficult time getting funding from Congress and O’Sullivan went on an expedition with Clarence King. In 1873-74, he went back to work for Wheeler, where they surveyed what is now known as the Four Corners area of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado.[7] During his second expedition with Wheeler, O’Sullivan’s photographs focused on Native Americans in the region, producing a series of images of villages, ruins, and the peoples of the region.

O’Sullivan is often considered to have created anti-aesthetic photographs, ignoring the contemporary conventions of beauty and the picturesque. Joel Snyder, in his essay “Territorial Photography” likens O’Sullivan’s work to gruesome and frightening photographs, creating an aesthetic of the West as an uninhabitable and harsh environment, unfriendly to perspective homesteaders. The images are considered stark and unappealing, as Snyder says: “This interior is presented as a boundless place of isolation, of contrasts of blinding light and deep, impenetrable shadows.”[8] The intriguing part of O’Sullivan’s work was that he was primarily interested in documenting a civil engineering project and his images served as survey images for reports that were created back East. O’Sullivan’s work was about collecting data for scientific surveys and not for intended commercial use. His intentions and aesthetics are in deep contrast to Watkins, who sold his images as tourist images and eventually even ran his own San Francisco gallery.[09]

Many of O’Sullivan’s photographs contain information about the survey process, in No. 8 Black Canon, Colorado River From Camp (fig. 3) the viewer is given data about not only the landscape, but also of the survey team. The man in the boat in the foreground is minute in relationship to the canyon walls and the river looks massive, as though waiting to swallow the man in the boat, showing his insignificance and the tools of the trade. And in Sand Dunes near Carson City (fig. 4) , it is the presence of O’Sullivan’s mobile dark room that truly adds the starkness to this photograph. Both of these images really give a sense of the topography of the region that he is located in because of the stark outlines of the geological forms in the images. O’Sullivan was very active in the entire survey process and assisted in collecting other types of specimens, as well as working on books and stereographic reproductions with Wheeler. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that O’Sullivan’s images were viewed in an artistic sense.

In 1939, landscape photographer Ansel Adams found a number of O’Sullivan’s prints and sent them to Beaumont Newhall, the curator of photography at the MOMA in New York. Newhall was intrigued by the images and decided to show the work; by doing so placed O’Sullivan’s prints in the legacy of modernist photography by focusing on the flatness, jarring use of light and dark, and the dominant geographic forms in his images.[10] Of course this placement is argued, Robin Kelsey attributes many of the “modern” elements to O’Sullivan’s work as being derived from his close work with other scientists and the graphic elements of survey documentation. No matter the outcome, O’Sullivan’s work has had a lasting effect on photographers and some of his influence, as well as that of Watkins, can be seen in the works of artists involved in the New Topographics group show that happened nearly a century after O’Sullivan’s work was created.

The New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape was a group show put together in January 1975 at the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY. The works collected in New Topographics embodied the changing face of America’s relationship with its landscape. Participants in the original show were: Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel. In 2010, the exhibition was restaged at a number of different museums, including the SFMOMA. Originally described as the intersection of fine art photography and conceptual art, the prints were stark, intentionally simple, most in black-and-white as if only “topological maps.”

The uniqueness of this show was its aesthetic. New Topographics was the anti-thesis of the sublime landscape; instead the photographs highlighted the human-impact on the landscape. The photographers documented recent urban and suburban developments, mining operations, dying and dusty small town main streets, abandoned factories, and discarded objects. Essentially these photographers captured America in its becoming rather than presenting an idealized or nostalgic view and there is a decided lack of pictorial or sublime elements to these works. The photographs are reminiscent of O’Sullivan’s haunting images, such as the Sand Dunes near Carson City, Nevada Territory (fig. 4), containing the stark and somewhat bleak interpretations of the landscape, although the subject matter had begun to change, it is easy to see the corollary elements.

It was clear by the mid-1970’s that the emerging environmental movement was proving influential and a growing cynicism about development and urban planning had set in. The impacts of the previous twenty-five years of rapid development across America had begun to be acknowledged. In the northeast and Great Lakes region, the process of deindustrialization was beginning to set in as well. In many ways, these photographers are almost the complete opposite of Watkins, instead of heralding progress, these artists represented the impact of industrialization that is neither inviting or heroic. Instead the images are reminders that the landscape is no longer beautiful, that civilization’s expansion is taking its toll. The photographers of the New Topographics show have a similar approach to Watkins, in terms of a somewhat scientific and objective way of recording the landscape, but instead of greeting progress they seem to mistrust it. It is possible to see this in the titles of the works, that are almost scientific in nature, generally noting the location of the image and the year. There are no lyrical titles, just the facts.

Robert Adams work from the 1970s such as Burning Oil Sludge, Colorado, 1974 (fig 5) and Mobile Homes, Jefferson County, 1973 (fig. 6) both emphasize the stark elements of what has been called the “New Topographics” aesthetic. Both images present a cold and somewhat scientific view of the rapidly changing landscape, the images are bleak and create a contrast between the natural element and the human hand. Burning Oil Sludge does not welcome progress, this image makes the viewer question why the oil sludge is on fire and the feel of revulsion of the huge plumes of black smoke and that must be detrimental to the local air quality. Culturally, these images reflect the changing perceptions of the landscape, as no longer a vast and open source of potential resources, instead it shows the actual impact of land use and the effects of the built environment.

Edward Burtynsky and Richard Misrach are two photographers that have a direct legacy to the photographers of the New Topographics and perhaps could be identified as the next generation of landscape photographers depicting the impact of civilization on the lands of North America. First there are a couple of distinct differences in the work, both Burtynsky and Misrach work in color images and generally print in large formats, on the same scale as Andreas Gursky, rather than the small and intimate black and white photos. Both of these artists work with images of the landscape, mostly those ravaged by industry. Burtynsky has worked in a variety of mining, manufacturing, and recycling centers, while much of Misrach’s work has focused on the desert of the Southwest and in the last couple of decades he has expanded to working in Louisiana, of particular note the haunting images of the Cancer Alley (fig. 11) series. ]Their work brings attention to often forgotten and unseen aspects of industrialization, reflecting the changes since the seventies of the global dialogue about environmental conservation, and the diminishing availability of natural resources. This is not the landscape of endless opportunity.

Aesthetically, Burtynsky and Misrach’s photographs are stunning (see figures 9-12). Their compositions and use of color are always inviting and the most powerful impact of the work is upon closer inspection, once the viewer begins to examine the large pictures, absorbing the minute detail in the prints. In many ways, their work harkens back to Burke’s ideas of the Sublime and how ugliness can be as powerful as beauty, these works are appalling in subject—yet gorgeous to look at. Both artists have been accused of aesthecizing horror11 or disaster, but the accusation amounts to a moralist’s dismissal and ignores the material conditions of contemporary photography; most successful artists have a developed aesthetic in their work—regardless of the subject matter, or the artist would not be commercially viable and therefore not considered successful.

It is interesting to look at the images by Burtynsky and Misrach in relationship to the images of Watkins. First there are some aesthetic considerations, the images of Burtynsky and Misrach both have a similar aesthetic sensibility as those of Watkins early Yosemite work, but instead of pristine nature the viewer is told to look at the remains of industry in an aesthetic way. Both artists are vocal about their interest in aesthetics in their work. Misrach in an interview in Art Papers told the interviewer that “against popular wisdom, I feel that aesthetics has a way of making things stick,” in reference to the question of aesthecizing horror. John K. Grande, in an article in Art Papers seems pretty annoyed that Burtynsky is interested in the Sublime and aesthetic beauty in his work and tries to place a judgment, going on to say that “The landscape Burtynsky captures in large format is hypnotic, and draws us in. An effect of beauty and toxicity builds a complex set of signals with dual signifiers, of good and evil, and Biblical messages.”[12] Grande wants to know to what end this set of dual signifiers helps the viewer digest these images, but even the idea of duality seems quite dated and if there is any power to these images, it is that they exist. Landscape is an always changing concept—rooted in historical reference only as much as the viewer is willing to accept that the landscape is in a constant state of flux. Idealizing the past ideals of landscape as pristine is as much a mistake as thinking that these contemporary images are “witnessing” contemporary events, since humans have been altering the landscape in North American for thousands of years.